The Solitude of Descartes

- InLibroVeritas

- 11 janv. 2021

- 4 min de lecture

Dernière mise à jour : 1 mai 2023

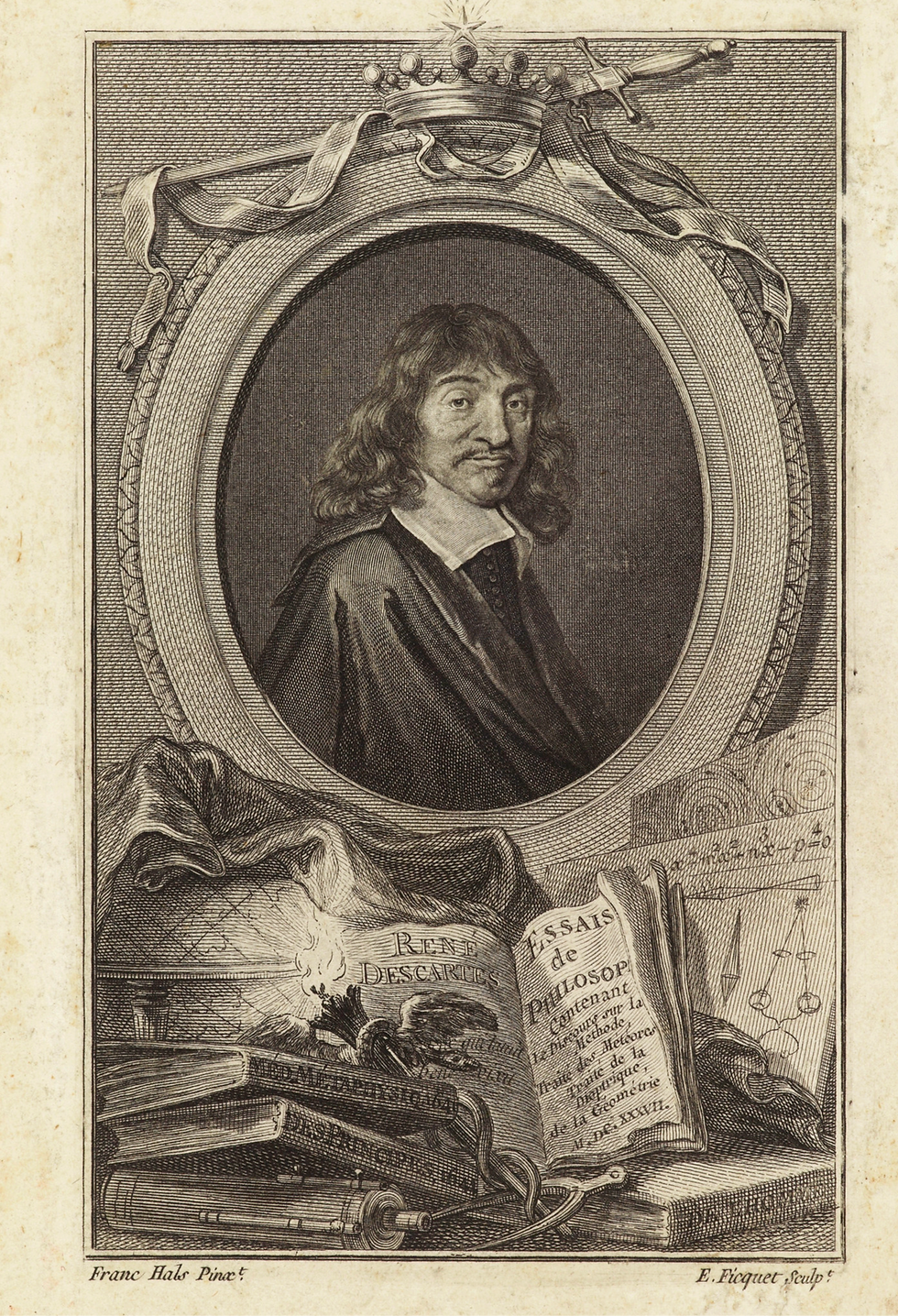

Portrait de René Descartes,

by Hals Frans (1580-1666)

Extract from:

William R. Alger

The Solitudes of Nature and Man

(1867)

P239

"The great Descartes, the pollen of whose thoughts, borne on all the breezes of inquiry, fertilized the philos ophy of Europe for two centuries, is a fine example of one who, in spite of brilliant accomplishments, extended reputation , strong affections, and courteous manners, was made essentially a solitary man by his intense devotion to the discovery of truth .

He repudiated traditional authority and prejudice, and with a sublime force and heroism of soul threw himself back on common sense and a sceptical openness and freedom of search for the reality of things. There are four ways in which most persons arrive at their various degrees of wisdom :

self-evident notions,

the experience of the senses,

the conversation of other men,

the reading of books.

There have been, Descartes says, in all ages, great minds who have tried to find a fifth road to wisdom, incomparably higher and surer than the other four, namely, the search of first causes and true principles from which may be deduced the reasons of all that can be known. On this fifth road few mightier travellers than he have ever trod. Those who have passed him since were in debted to his guidance. He dared to strip off all past beliefs that he might not be encumbered or misled.

“But”, he says, "like one walking alone and in the dark, I resolved to proceed so slowly and with such circumspection that if I did not advance far, I would at least guard against falling.”

Regarding “the supreme good as nothing more than the knowledge of truth through its first causes”, he allowed nothing to interfere with his pursuit of it. But his kind temper, good taste and prudence did not disarm the fears and foes awakened by the boldness of his speculations. Stratagems and dangers surrounded him.

Cousin says, “After having run round the world much, studying men on a thousand occasions, on the battle-field, and at court, he concluded that he must live a recluse. He became a hermit in Holland.”

Eight years later he writes.

"Here, in the midst of a great crowd actively engaged in business and more careful of their own affairs than curious about those of others, I have been enabled to live without being deprived of any of the conveniences to be had in the most populous cities, and yet as solitary and as retired as in the midst of the most remote deserts."

At another time, he says,

“I shall always hold myself more obliged to those through whose favor I am permitted to enjoy my retirement without interruption than to anyone who might offer me the highest earthly preferments."

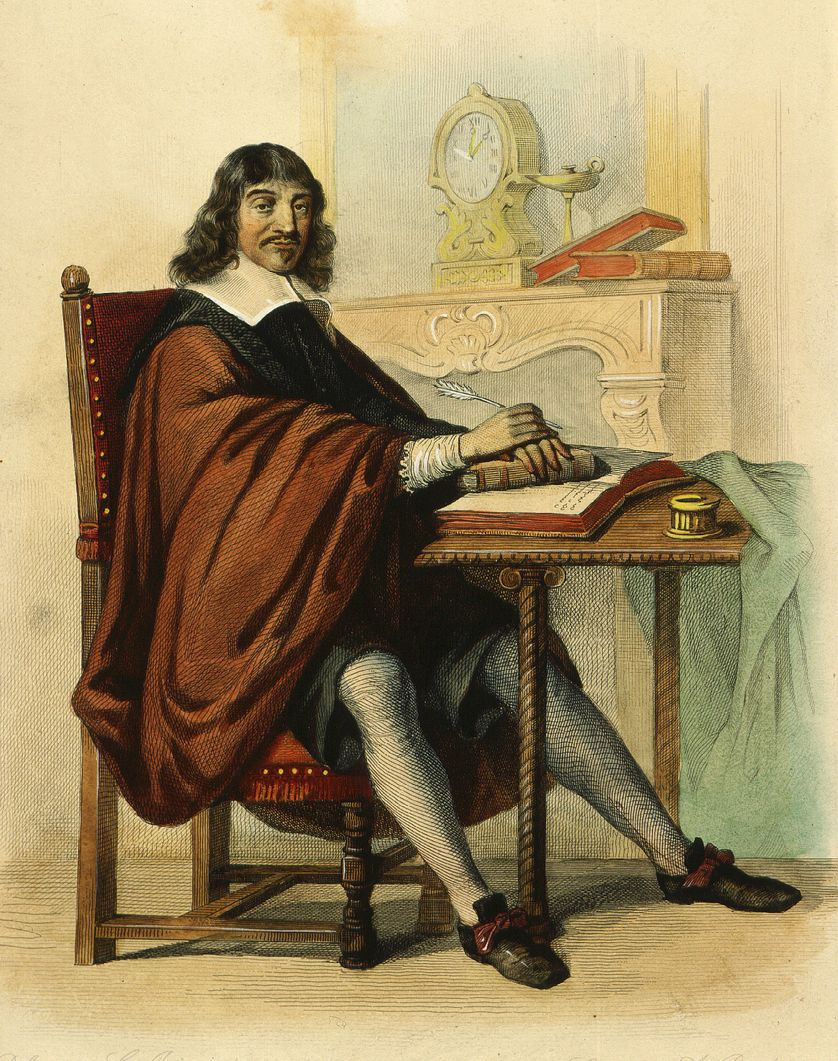

René Descartes (1596-1650), par C. Jacquand

Gianni Dagli Orti / The Art Archive

There is no reason to doubt the sincerity of this declaration ; yet there is another side to the truth. For when Queen Christina paid him honoring attentions, and invited him to her court at Stockholm, he went thither and occupied an academic post. His first passion was the pursuit of truth ; his second, a love of the esteem of his fellow men. His own frank words give a pleasing proof of this.

“My disposition making me unwilling to be esteemed different from what I really am, I thought it necessary by all means to render myself worthy of the reputation accorded to me. This desire constrained me to remove from all those places where interruption from any of my acquaintances was possible, and to give myself up to studies.”

There was no misanthropic ingredient in his isolation. Yet, once or twice, a little soreness, a little petulance at the neglect of the public, at the lack of the cooperation he needed, escapes him.

“Seeing that the experiments requisite for the verification of my reasonings would demand an expenditure to which the resources of a private individual are inadequate, and as I have no ground to expect public aid, I believe I ought for the future to content myself with studying for my own instruction, and posterity will excuse me if I fail to labor for them.”

But if, contrary to his own opinion, the ambition of Descartes in relation to society and mankind was superior to his fruition, so that some dissatisfaction resulted, it did not sour or exasperate him . On the whole, he kept his moral equipoise well and sweetly. He has himself indicated his three great re serves of happiness.

First, his employment itself.

“The brutes, which have only their bodies to conserve, are continually occupied in seeking sources of nourishment ; but men, of whom the chief part is the mind, ought to make the search after wisdom their principal care ; for wisdom is the true nourishment of the mind."

“Although I have been accustomed to think lowly enough of myself, and although when I look with the eye of a philosopher at the varied courses and pursuits of mankind at large, I find scarcely one which does not appear vain and useless, I nevertheless derive the highest satisfaction from the progress I conceive myself to have already made in the search after truth, and cannot help entertaining such expectations of the future as to believe that if, among the occupations of men as men, there is any one really excellent and important, it is that which I have chosen."

Second, intercourse with the highest minds of all times and countries.

“The perusal of excellent books is, as it were, to enjoy an interview with the noblest men of past ages, who have written them, and even a studied interview in which are discovered to us only their choicest thoughts."

And thirdly, the subjection of his wishes to his condition.

“My maxim was always to endeavor to conquer myself rather than fortune, and change my desires rather than the order of the world, and, in general, to accustom myself to the persuasion that, except our own thoughts, there is nothing absolutely in our power. Thus we learn to regret nothing which is unchangeable, desire nothing which is unattainable.

I confess there is need of prolonged discipline and repeated meditation to accustom the mind to view all objects in this light ; and I believe that in this chiefly consisted the secret of the power of such philosophers as in former times were enabled to rise superior to the influence of fortune, and, amid suffering and poverty, enjoy happiness which their gods might have envied.”

* * *

Source :