Irène de Palacio

il y a 18 heures

Dernière mise à jour : 11 sept. 2022

From the frontispiece H. Peacham's "Minerva Britannia"

(1851)

THE CLUE TO THE MYSTERY OF BACON'S LIFE

The theory now put forward is based upon the assumption that Francis Bacon at a very early age adopted the conception that he would devote his life to the construction of an adequate language and literature for his country and that he would do this remaining invisible. If he was the author of "The Anatomic of the Mind," 1576, and of " Beautiful Blossoms," 1577, he must have adopted this plan of obscurity as early as his sixteenth year.

"Therefore, set it down," he says in the essay Of Simulation and Dissimulation, "that a habit of secrecy is both politic and moral," and in Examples of the Antitheta

"Dissimulation is a compendious wisdome."

Here again is the same idea :

"Beside in all wise humane Government, they that sit at the helme, doe more happily bring their purposes about, and insinuate more easily things fit for the people by pretexts, and oblique courses ; than by downright dealing. Nay (which perchance may seem very strange) in things meerely naturall, you may sooner deceive nature than force her ; so improper and selfeimpeaching are open direct proceedings ; whereas on the other side, an oblique and an insinuating way, gently glides along, and compasseth the intended effect. "

It is noteworthy that Bacon had a quaint conceit of the Divine Being which he was never tired of repeating. In the preface to the "Advancement of Learning" (1640), the following passage occurs :

— " For of the knowledges which contemplate the works of Nature, the holy Philosopher hath said expressly ; that the glory of God is to conceal a thing, but the glory of the King is to find it out : as if the Divine Nature, according io the innocent and sweet play of children, which hide themselves to the end they may be found ; took delight to hide his works, to the end they might be found out ; and of his indulgence and goodness to mankind, had chosen the Soule of man to be his Play-fellow in this game."

In the author's preface to the "Novum Organum" the following passage occurs :

— "Whereas of the sciences which regard nature the Holy Philosopher declares that 'it is the glory of God to conceal a thing, but it is the glory of the King to find it out.' Even as though the Divine Nature took pleasure in the innocent and kindly sport of children playing at hide and seek, and vouchedsafe of his kindness and goodness to admit the human spirit for his play fellow in that game."

The close connection of Francis Bacon with the works of the Emblem writers is vouched for by J. Baudoin. Oliver Lector in " Letters from the Dead to the Dead" has given examples of his association with the Dutch and French emblem writers.

Three Englishmen appear to have indulged in this fascinating pursuit — George Whitney, Henry Peacham, and George Withers. From the Baconian point of view Peacham's " Minerva Britannia" is by far the most interesting. The Emblem on page 34 is addressed "To the most judicious and learned, Sir Francis Bacon Knight." On the opposite leaf, paged thus, 33*, the design represents a hand holding a spear as in the act of shaking it.

[*33 is the numercial value of the name " Bacon." The stop preceding it denotes cypher.]

But it is the frontispiece which bears specially on the present contention. A curtain is drawn to hide a figure, the hand only of which is protruding. It has just written the words

"Mente Videbor"

"By the mind I shall be seen."

Around the scroll are the words

"Vivitur ingenio cetera mortis erunt."

"One lives in one's genius, other things shall be (or pass away) in death".

That emblem represents the secret of Francis Bacon's life. At a very early age, probably before he was twelve, he had conceived the idea that he would imitate God, that he would hide his works in order that they might be found out — that he would be seen only by his mind and that his image should be concealed.

There was no haphazard work about it. It was not simply that having written poems or plays, and desiring not to be known as the author on publishing them, he put someone else's name on the title-page. There was first the conception of the idea, and then the carefully elaborated scheme for carrying it out.There are numerous allusions in Elizabethan and early Jacobean literature to someone who was active in literary matters but preferred to remain unrecognised. Amongst these there are some which directly refer to Francis Bacon, others which occur in books or under circumstances which suggest association with him. It is not contended that they amount to direct testimony, but the cumulative force of this evidence must not be ignored.

(...)

In the " Mirrour of State and Eloquence," published in 1656, the frontispiece is a very bad copy of Marshall's portrait of Bacon prefixed to the 1640 Gilbert Wat's "Advancement of Learning." Under it are these lines :

"Grace, Honour, virtue, Learning, witt.

Are all within this Porture knitt

And left to time that it may tell,

What worth within this Peere did dwell."

The frontispiece previously referred to of "Truth brought to Light and discovered by Time, or a discourse and Historicall narration of the first XIIII yeares of King James Reign," published in 1651, is full of cryptic meaning and in one section of it there is a representation of a coffin out of which is growing

"A spreading Tree

Full fraught with various Fruits most fresh and fair

To make succeeding Times most rich and rare."

The fruits are books and manuscripts.

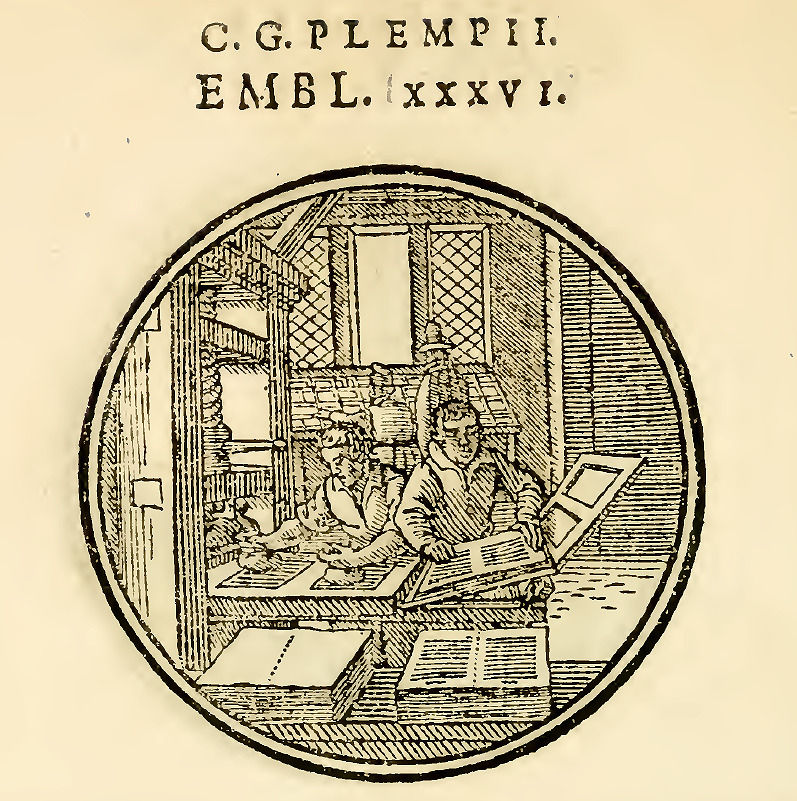

A suggestive emblem is No. I of Cornelii Giselberti : Plempii Amsterodarnum Monogrammon, bearing date 1616, the year of Shakepeare's death. It is now reproduced. It will be observed that the initial letters of each word in the sentence — Obsccenumque Nimis Crepint Fortima Batavis Appellanda — yield F. Bacon.

There are in other designs figures which are evidently intended to represent

Bacon. Emblem XXXVI. shows the inside of a printer's shop and two men at work in the foreground blacking and fixing the type. Behind is a workman setting type, and standing beside him, apparently directing, or at any rate observing him, is a man with the well-known Bacon hat on.

The contention may be stated thus : — Francis Bacon possessed, to quote Macaulay, "the most exquisitely constructed intellect that has ever been bestowed on any of the children of men." Hallam described him as "the wisest, greatest of mankind," and affirmed that he might be compared to Aristotle, Thucydides, Tacitus, Philippe de Comines, Machiavelli, Davila, Hume, "all of these together," and confirming this view Addison said that "he possessed at once all those extraordinary talents which were divided amongst the greatest authors of antiquity."

At twelve years of age in industry he surpassed the capacity, and, in his mind, the range of his contemporaries, and had acquired a thorough command of the classical and modern languages. "He, after he had survaied all the Records of Antiquity, after the volumes of men, betook himself to the volume of the world and conquered whatever books possest." Having, whilst still a youth, taken all knowledge to be his province, he had read, marked, and absorbed the contents of nearly every book that had been printed. How that boy read !

Points of importance he underlined and noted in the margin. Every subject he mastered — mathematics, geometry, music, poetry, painting, astronomy, astrology, classical drama and poetry, philosophy, history, theology, architecture. Then — or perhaps before — came this marvellous conception,

"Like God I will be seen by my works, although my image shall never be visible — Mente videbor. By the mind I shall be seen."

So equipped, and with such a scheme, he commenceed and successfully carried through that colossal enterprise in which he sought the good of all men, though in a despised weed. "This," he said, "whether it be curiosity or vainglory, or (if one takes it favourably) philanthropia, is so fixed in my mind as it cannot be removed."

Sources :